“Are Easter Eggs All They’re Cracked up to Be?”

I’ve always loved dyeing Easter Eggs. Every year my Nana would take my sister and me to the Dollar Store to get the classic “Paas” egg-dyeing kits and we would spend all afternoon dyeing dozens of eggs.

So as spring started to approach, I began to think about all those eggs and wondered where this tradition of egg-dyeing started. How did we start taking seemingly boring, white eggs and turning them into bright and colorful symbols of love for friends and family? Well after some research I’ve discovered that the egg is not only a token object for Easter and Spring celebrations but they have been an instrumental part of history for centuries.

Spring is the beginning of a new season full of plants blooming and rebirth. So it is no wonder that a holiday celebrating the resurrection of Jesus Christ would also take place at the beginning of spring. But Christianity is not the only religion to take credit for Easter celebrations. Back in Medieval Europe, there was an early Anglo-Saxon festival “Eostre”. This celebration was in hopes to gain favor with the goddess of fertility and “the resurrection of nature after winter” stated Carole Levin, Professor of History and Director of the Medieval and Renaissance Studies Program at the University of Nebraska.

Professor Levin goes on to say that once missionaries began to make their way around the globe, most of them hoped that celebrating their Christian holy days at the same time as Pagan festivals would eventually lead to conversions to Christianity. This would be especially true if the symbols carried over and eggs happened to be a large part of both celebrations. It is said that eggs were eaten at the “Eostre” festival and even buried in the ground to encourage fertility. For early Christianity, during Lent, they were forbidden to eat animal products, including eggs. So farmers would hard-boil them for a later time.

Christianity is not the only modern religion to celebrate Easter. In the Jewish tradition, the connection between Easter and Passover goes much deeper than eggs. As previously stated, the word Easter comes from the pagan festival “Eostre”, but many languages use a Passover or “Pesach”. And those classic “Paas” egg-dyeing kits I mentioned earlier were named after the Dutch word for Easter, “Pasan”. This web of origin stories reminds us that even though many associate colorful Easter Eggs with Christianity, they actually extend far beyond any one denomination. So how did we actually start coloring them? Well, historians debate that one of the earliest sights of dyed eggs was back in 1290.

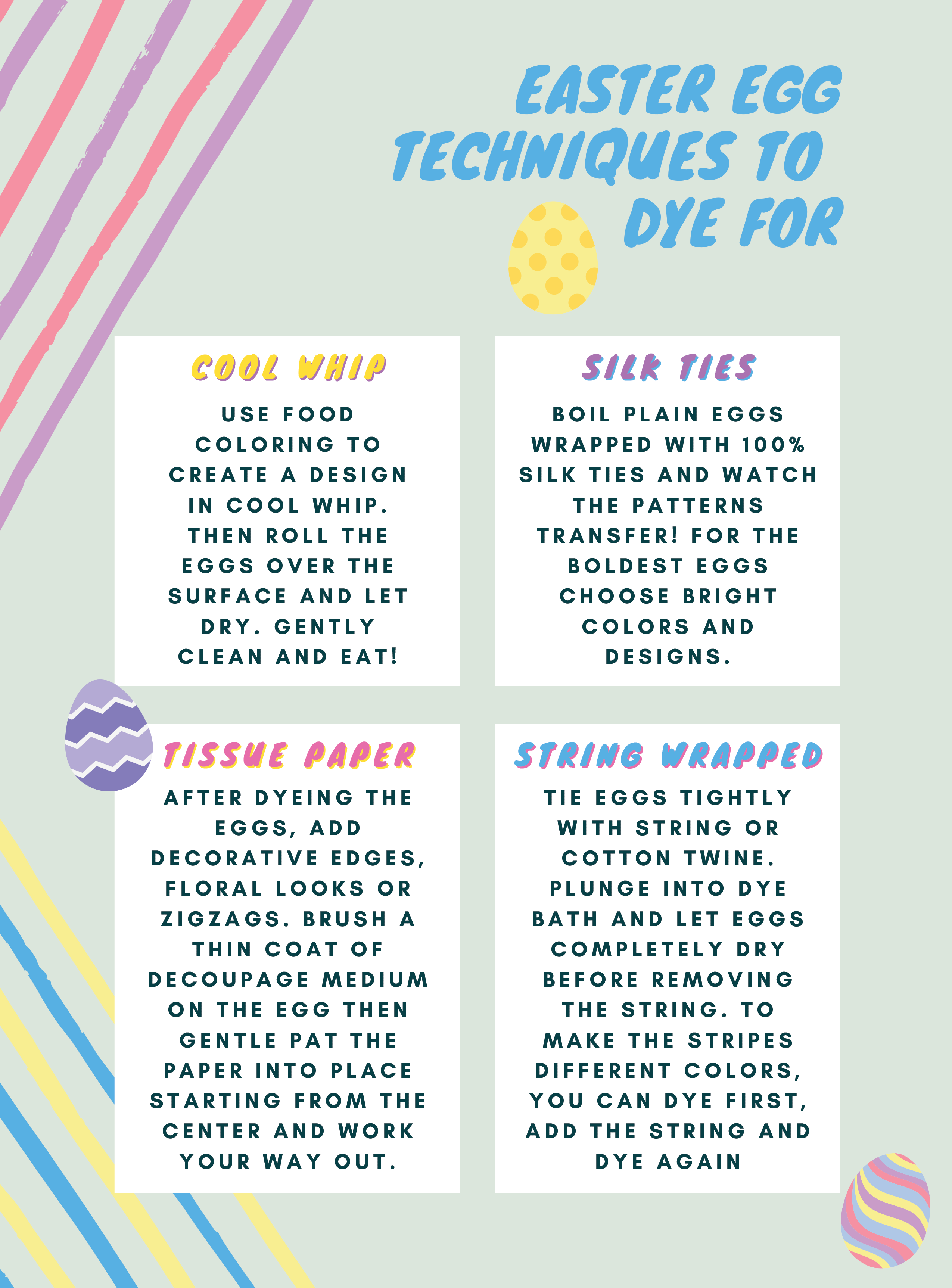

In British history, the household of Edward I bought 450 eggs to be covered in gold leaf and then handed out among the fellow nobility for Easter, according to Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain by Ronald Hutton. Now by the 13th century, residents of English villages brought Easter Eggs to their landlords and churches as a special offering on Good Friday. These eggs were often colored red as a color to signify joy. In the late 19th and early 20th century is where we begin to see dyeing Easter eggs as something to give to children instead of the church. The 19th century is also where we started to see the most famous decorated eggs to date - the elaborately jeweled Faberge eggs. By the first half of the 20th century, the working class also began adopting these egg-coloring traditions as their wages increased, and here we are today, with so many different techniques to dye eggs!